Seattle U Students Help Pass Gender-Inclusive Housing Policy

Seattle University prides itself on its diverse student population and drive to achieve social justice through education of the whole person.

Seattle U has had a historically inclusive attitude towards those who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. However, in the past decade, there has been a shift among the student population: a call to the administration from Seattle U’s transgender, non-binary, and gender non-conforming students for an increase in resources and for more accommodating housing.

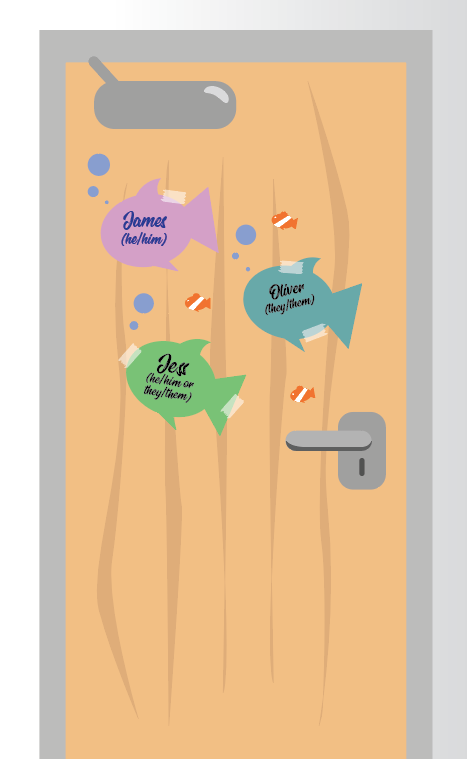

Seattle U’s new inclusive housing policy is stated on the university’s website as follows: “Transgender, gender non-conforming, and non- binary students have the option to live with students who share their gender identity, correct their gender identity, name, and pronouns… [in] the housing portal, and use the housing portal to be matched with roommates who share their or affirm their gender identity.” Below this statement is a short glossary of terms like “transgender” and “non-binary” to educate unfamiliar students.

This policy took over 10 years of discussion and working groups to be officially approved. In 2009, it came to the attention of housing officials that increasingly more students were requesting system name changes or a roommate switch so they could live with a student who matched their gender identity or someone they felt more comfortable with.

The former housing policy and online portal operated on a male-female binary system, where roommates were paired together based on their biological sex. Students would apply to Seattle U under their legal name, with zero opportunities to enter their preferred name. For many transgender students, moving into a new dorm labeled with their legal, or “dead name,” can be a traumatic start to college.

Ash Joyce, a second-year student who identifies as non-binary, spoke to their experience with inconsistencies in the system.

“When I moved in this year, my RA had to specifically ask me what name I went by,” Joyce said. “I’m glad that she knows that I go by a different name, but she didn’t know what it was because it wasn’t in the system.”

“When the system shows the wrong name, it honestly feels like a microaggression. It’s transphobia. Even if it’s not intentional, it’s still very real.”

Eight years ago, the first official inclusive housing policy was drafted. It was repeatedly sent up the chain of command with no luck.

Associate Director of Housing and Residence Life (HRL) Tim Albert has worked with students to accommodate their needs.

“There was some concern because it [is] a Catholic school,” Albert said. “Some of the politics within the Church made it difficult.”

This process of rewriting, waiting, and sending the drafts up for approval yet again was slow, and it frustrated the students involved. In Feb. 2018, a group of student activists formed the Gender Inclusive Housing Council. According to the presentation they gave to department heads, this group strives to “create a more trans, non-binary, and queer-inclusive environment on campus.”

The main policy changes that this group demanded were adjustments to the housing portal, faculty and housing employee training, and most importantly, “creating more accountability for staff in charge of imposing housing policy.”

Students celebrate the passing of the new gender-inclusive housing policy.

In April 2018, Triangle Club, a student-led campus organization group that supports LGBTQ+ students, hosted their annual drag show. The Spectator published a story the following week covering the event, placing a picture of one of the student performers on the front cover to showcase the article.

Right before an admissions event where prospective students and their families visited the campus, a resident Jesuit admitted to removing countless copies of the newspaper from their holders around campus, saying he was worried the new students would be offended by the content. University President Father Stephen V. Sundborg S.J. made a statement concerning the events, but many students felt that his show of support was insincere.

Backlash ensued among the student body, and HRL scrambled to answer complaints and concerns. With the student body reeling from events they felt revealed the administration’s lack of support, it was in this chaotic time that the most progress was made on the gender inclusive housing policy.

“[This] drama created a climate where we got to do some things weren’t really allowed to do before,” Chris McCarty, assistant director of HRL, said.

HRL was given permission to begin drafting an official policy that had the promise to be approved more quickly than in previous years. After student feedback seminars, collaboration with the Office of Multicultural Affairs and the Gender Justice Center, and three different drafts, the new policy was formally approved by Seattle U and posted on the website in February 2018, making the university the third Jesuit college in the country to have gender inclusive housing. This was a triumph for students who had been working hard to convince the school the policy was necessary.

“You [should not] need to talk to an administrator to get the same thing that most other students can have easily… Changing the system is difficult; it is hard to find a system that gives students options and flexibility without throwing out the binary for everyone.”

President of Triangle Club Ames Zocchi was one of the student activists involved in creating the gender inclusive housing policy.

“I’m really happy and proud of this actual thing happening,” Zocchi said. “I was honestly really scared [it wasn’t going to pass] and it was really hard to get in contact with folks in the administration to see if this was going to happen or not.”

Zocchi spent copious amounts of time working with HRL officials and joked that he is “probably on their watch list by now.” While Zocchi understood that making bureaucratic change on campus was not going to happen instantly, he found the process tireless.

“There’s blame to go all around here for why gender-inclusive housing hasn’t happened sooner,” Zocchi said. “Housing tried, but they didn’t have the tools available to them, and they didn’t look for the tools. But if they opened the drawers and did some work, they would’ve found them.”

Another important feature of the new housing policy is the ability for students to change their name in the online system to their preferred name. This was good news for Joyce, who single-handedly assembled a user- friendly guide for students to learn how to switch their legal name to their preferred name in all Seattle U systems, which is usually a long and complicated process.

“When the system shows the wrong name, it honestly feels like a microaggression. It’s transphobia. Even if it’s not intentional, it’s still very real.” Joyce said.

Joyce has been at Seattle U for two years and continually runs into new places in the myriad systems where their legal name is shown instead of their preferred name, a name that virtually everyone on campus knows them by. Joyce thinks the new housing policy is “a step in the right direction,” but still feels there is more work to be done.

The gender-inclusive policy has passed, but there is still room for improvement. McCarty is working hard on improving the housing portal in time for the incoming first-year class to register. McCarty wants to customize the portal so everyone can apply for housing the same way, regardless of gender identity.

“You [should not] need to talk to an administrator to get the same thing that most other students can have easily,” McCarty said. “Changing the system is difficult; it is hard to find a system that gives students options and flexibility without throwing out the binary for everyone.”

Housing is also currently working on a guide for students to show accessible resources on campus, such as where the gender-neutral bathrooms are located and specific features of each residence hall.

As the newest incoming class is scheduled to register for housing soon, the future is still yet to be written.

“I have welcomed a lot of younger students to make sure they know and keep [the fight for gender justice] going,” Zocchi said. “It’s not going to die out.”

The editor may be reached at

[email protected]

Karen Chin

Jun 24, 2021 at 2:03 pm

Thank you for this article. I’d be interested to learn what the current experienced is for trans students. My trans son is considering Seattle University and I am concerned about the housing and culture there, especially because the school is not part of the Campus Pride Index, which has helped understand some basics about a school. Has anyone at Seattle University asked the school to be part of the Campus Pride Index?