Describe your favorite professor.

Don’t think about it too hard, just let the adjectives fly. How would you describe them to someone who had never met them before?

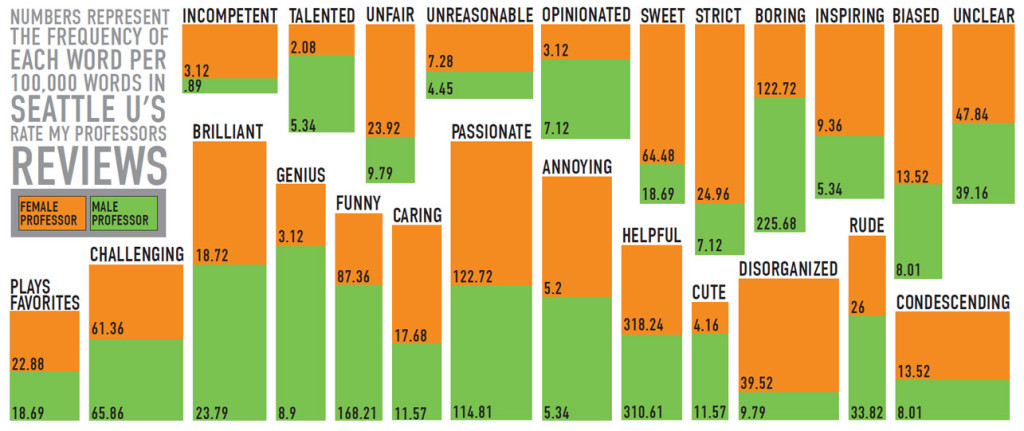

Were they funny, brilliant, and talented? If so, then statistics show that you’re more likely to be thinking of a man.

Caring, passionate, and sweet? Probably a woman.

A professor at Northeastern University recently created an interactive graph that showed the significant differences in language used to describe male and female professors. You’ve probably seen it making the rounds on social media lately.

Inspired by this, we here at the Spectator have spent the past week analyzing Seattle University’s own Rate My Professors page. We compiled all the ratings, all the reviews (or the top 10, for extra-popular professors), and yes, all those little red chili peppers into one massive document, which we could then use to look up any word we wanted.

What started as a fun experiment ended up giving us a revealing, fascinating, and sometimes disturbing look at the hidden biases that underlie faculty-student relationships at this (and every) university—biases that take root within, but can cause very real damage.

By Caroline Ferguson

With additional reporting by Vikki Avancena, Lena Beck, Jason Bono, Jenna Ramsey and Siri Smith.

It all comes down to James Bond and Mother Duck.

Okay, in academic terms they’re called masculine-agentic and feminine-communal traits. But Seattle U Faculty Development Consultant Therese Huston, who is currently studying women and decisionmaking, prefers James Bond and Mother Duck.

Simply put, men are expected to play the part of the savvy, brilliant, freewheeing badass at all times. They’re supposed to be charming, funny, and cool. When male professors fall short, they fall short in relation to these attributes. Sure enough, the go-to criticism for male professors (if Seattle U’s Rate My Professors page is to be believed) is that they’re too boring. James Bond should never be boring, right?

As for women, as Huston puts it, “they’re supposed to be caring and emotional and devoted to others, and paying attention to how everybody’s feeling.” The negative feedback they receive, she says, often boils down to the idea that “they’re not being enough of a mother duck—they’re too strict, they’re too mean.”

Much of what we know about gender stereotyping boils down to these two sets of expectations, which most of us hold on to whether we know it or not.

Sure enough, female professors at Seattle U are called strict on Rate My Professors more than three times as often as male professors are, and they’re most often praised for their emotional strengths: their care for students, their sweetness, their passion for teaching.

Though the legitimacy of Rate My Professors is certainly debatable, Seattle U’s University Rank and Tenure Committee chair Dr. Jodi O’Brien said that the biases it reveals seem to be largely consistent with research on gender and academic evaluations. Approximately 75 peer-reviewed studies a year are published on the subject, according to Center for Faculty Development Director David Green.

For example, research shows that female professors who go out of their way to help students tend to be seen as meeting expectations, whereas male professors who do so are seen as going above and beyond the call of duty.

“There’s a different baseline in terms of availability, helpfulness, and so forth,” O’Brien said. “That’s one thing that’s really clear.”

This double standard also manifests in non-academic workplaces According to a Feb. 6 article by Adam Grant and Sheryl Sandberg in the New York Times’ Women at Work column, research has shown that women tend to exhibit more helpful behaviors in offices but benefit less from it.

“When a man offers to help, we shower him with praise and rewards,” the authors wrote. “But when a woman helps, we feel less indebted. She’s communal, right? She wants to be a team player.”

Another subconscious assumption that tends to reveal itself in evaluations is that women lack expertise. Essentially, male professors are assumed to be authoritative unless they show otherwise, whereas women more often have to prove that they are worthy of being listened to. Women, therefore, are more likely to have their competence called into question in the classroom, in course evaluations, and on Rate My Professors, where female professors are more likely to be called disorganized, unfair, unreasonable, and incompetent.

These biases aren’t just internal, though. They occasionally manifest in the form of disruptive and disrespectful student behaviors, known in some academic circles as classroom incivilities. According to Green, professors who experience overlapping oppressions—a part-time female professor, for example, or a faculty member of color who is the minority gender in their discipline—are particularly susceptible to this kind of undermining behavior from students.

Associate professor Dr. Pamela Taylor has experienced this firsthand.

“Being a person of color—specifically African descent—and female-identified comes with certain perceptions [from] male students and of white students,” Taylor said.

Taylor’s classroom policies have been questioned, challenged, and dismissed as unfair by her students. She’s received scathing emails and in-person admonitions from members of her classes.

“I know they don’t do that with other professors who are not people of color and who are not female,” Taylor said.

Professor and Math Department Chair Allison Henrich has also been on the receiving end of student frustration.

“I do feel like I’ve been subject to anger from students that is misguided,” Henrich said. “I know several female math professors who have trouble keeping order in their class, and I think very few male professors in the department have problems like that. They automatically get some sort of respect without having to do much to earn it.”

The Center for Faculty Development’s work is confidential, so Green could not divulge the frequency and severity with which Seattle U’s professors experience classroom incivility—though he did say that he occasionally sees inappropriate comments in evaluations.

Though it’s harder to quantify on sites like Rate My Professors, faculty members of color are also at a disadvantage when it comes to course evaluations and classroom incivilities—and women of color are doubly affected.

Presumed Incompetent, a book published in 2012 and co-edited by Seattle U professor Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs, explores the intersections of race, gender, and class for women in academia. An entire chapter, written by Sylvia R. Lazos of UNLV, focuses on student evaluations.

“[Women and minority] professors must walk a narrow pathway to manifest their gender and race and balance their teaching goals,” Lazos writes. “They must maintain their individual authenticity in the classroom and yet avoid alienating students who—even at this late date—may not have encountered a minority authority figure in a professional setting.”

O’Brien also noted that women of color who address social justice issues in the classroom often face harsher criticism for it. She’s used to reading evaluations that disparage women in her department who teach about oppression and privilege, while their male colleagues are praised for doing the same.

“Women and faculty of color, when they teach content in the social sciences or something, are seen as ‘political’ and ‘having an agenda,’” O’Brien said. “Men who teach exactly the same content are seen as wise and experts in their field and passionate about their research.”

O’Brien’s claim checks out. Once again, Seattle U’s Rate My Professors responses echo the anecdotal evidence and research: overwhelmingly, male professors are called “opinionated,” whereas their female counterparts are “biased.”

The question no longer seems to be whether gender and race affect faculty evaluations, but rather how to ensure that female faculty and faculty members of color are being fairly assessed in light of overwhelming evidence showing that they are at a disadvantage. Expert opinions vary on how best to account for biased language and make sure it doesn’t damage careers.

Huston said that asking the right questions can make all the difference. Open-ended questions—for example, “would you recommend this professor?”—are subject to many different interpretations, not all of which are fair and valid. Students may give a professor a negative review because their class was early in the morning, or the instructor had an abrasive voice.

On the other hand, low-inference questions (“did this instructor provide feedback on a timely basis”) are less prone to receiving biased responses, Huston said. Asking whether professors performed certain behaviors, instead of about the student’s general feelings toward the professor, could result in fairer evaluations.

O’Brien disagreed that low-inference questions are the solution to the problem, because students tend to force themselves into an arbitrary opinion when prompted for one.

“If you ask [students] a question and it’s on a survey, they treat it as legitimate. So they’ll have an opinion whether they have any evidence or not,” O’Brien said.

According to O’Brien, making sure that those who process student feedback—the evaluators of the evaluators, if you will—are educated about bias can help them to contextualize responses and ensure that faculty are assessed fairly. Accordingly, the current University Rank and Tenure Committee is well aware of the biases and prejudices that can underlie student evaluations, and they try to take them into account when assessing tenure cases.

“If you don’t have department chairs and personnel committees that can read [bias], it can have consequences for how a person is evaluated,” O’Brien said. “We have a pretty good tenure committee right now … you have to learn how to read and interpret the narrative comments.”

If you ask Dr. Taylor, though, no revamp of the current evaluation system would be enough. What we need, she argues, is a total overhaul.

“It’s an archaic system based on institutional structures several hundred years old … when this thing was designed there were no women or people of color in higher education,” Taylor said.

Now, describe your favorite professor. And think a little harder this time.

Caroline may be reached at [email protected]