With spring comes craptons of sniffly noses and weepy eyes. Not because of sadness (generally?) but because of those darn pesky pieces of plant and animal floating around everywhere and getting themselves stuck up people’s noses and airways. Allergies. Ugh.

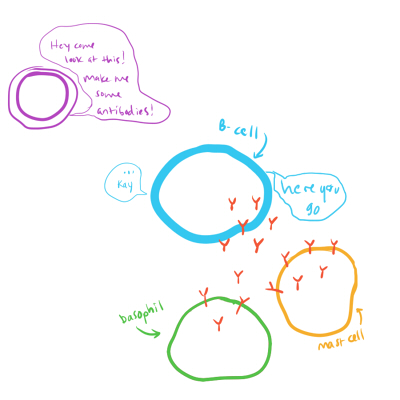

How the immune system gets all hyped up over pathogens as illustrated by blobs.

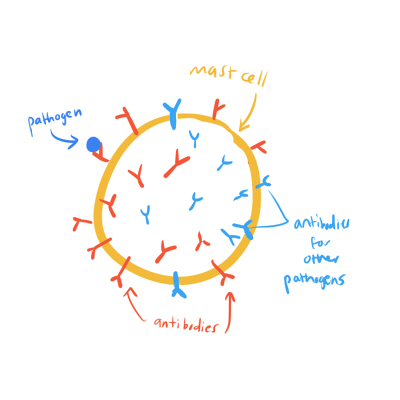

An allergy is an immune response. It happens when your immune system really, really hates something foreign and overreacts. When a pathogen enters the body, little proteins on the surface of mast cells and basal cells have specific sequences that just happen to complement the pathogen, making them stick together to the surface of the cell to make it more likely to get picked up by another cell. These are called antibodies. The first time around, that’s all that happens. No allergic reaction, no death, no anaphylaxis. Just preparation for the next attack.

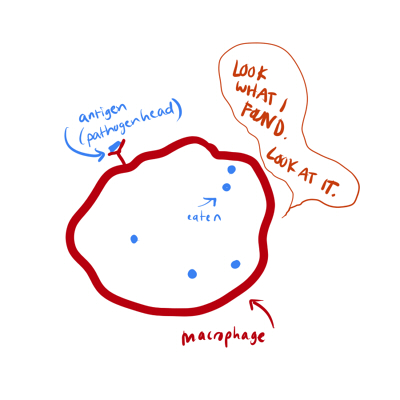

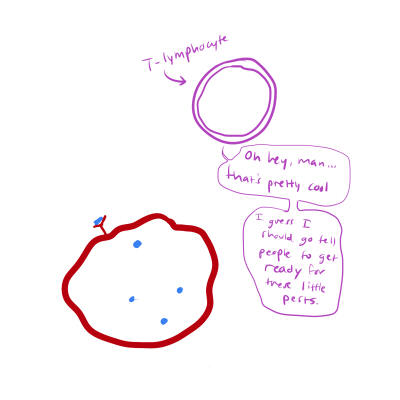

The immune system is like a tiny warzone. The first pass is the recon mission, and the next step is the preparation and gathering of troops. After the first encounter, big search-and-destroy cells called macrophages roam around and eat up all the remaining pathogen, but rip off the “heads” of the pathogen and stick it on its cell surface, as though they were parading around the heads of their enemies for the world to see. T-lymphocytes, another immune cell, will “see” those little heads, then signal other cells like B-cells (memory cells) to secrete antibodies that attach to the membranes of the other types of immune cells, like the mast cells and basophils mentioned earlier that act as patrol cells.

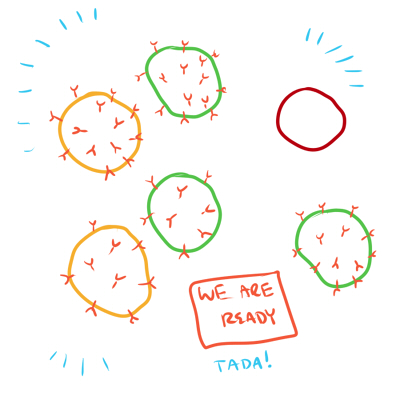

When the pathogen makes its appearance again, the body is ready. It knows what the pathogen is, knows how to identify it because it has more antibodies, has enough resources to do something about it, and is ready to defeat it. Mast cell activation occurs at the second exposure. The antibodies on the mast cells recognize the pathogen and bind to it, preventing that pathogen from escaping. It has become a prisoner. This binding causes a complex protein cascade that allows calcium into the cell, therefore allowing the mast cell to release its storage packets of terrible poisons and weapons of mass destruction out into the environment. Well, it’s not exactly terrible poison. It’s actually not a weapon at all. It’s a molecule called histamine, as well as a jumble of a bunch of other mediator molecules like platelet-activating factor.

Histamine is the main reason we have the typical allergic reaction. You can thank it for the redness, swelling, and inflammation. Other molecules are responsible for the airways tightening up, or the widening of blood vessels. Once all this molecular warfare is going on, other cells are called to the scene to help out with eating things, making the area more hot, and generally making a huge mess of things. Sometimes, so many cells are continuously called to the area that an allergic reaction can last for days at a time, even when a pathogen is totally gone from the system (or is still there, but only in small amounts).

Our body’s overvigilance can be quite annoying. Anaphylaxis is a general term for the severe allergic reactions, including skin rash or hives, swelling, heart problems, and shortness of breath. Anaphylactic shock is when the blood vessels dilate so much that the blood pressure shoots down to a pressure 30% lower than their normal baseline (this is very bad and can result in deadness). Norepinephrine is administered because it tells everything to tighten back up; the main function of norepinephrine is to excite things and get them ready for movement. It’ll make the vessels more rigid, the heart more active, and lots of other things to make you ready to escape or kick some butt. Norepinephrine during an allergy attack, then, reverses the effects of the histamines and forces the body to revert back to a normal state, thus saving someone from dying from something stupid like peanuts.

————————-

End notes:

1. I just want to mention that this is extremely different from being intolerant of something. Many people I know have said they are allergic to milk or shellfish when in reality, they don’t have any sort of immune response; they just lack the proper enzymes to break down the products effectively, resulting in gastrointestinal problems and a whole world of uncomfortableness. But that pollen that so lovingly crawls into our bodies uninvited? That’s an allergic reaction that gets our immune systems up and going.

2. In case you like slightly offensive but really funny stuff on allergies…Louis CK on Allergies